You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

MLB 2025

- Thread starter kane

- Start date

Way too much Red Sox love, that makes me nervous

Baltimore seemingly ignored.

Murphy’s Best

EOG Dedicated

Orioles pitching is the big question this season…

Murphy’s Best

EOG Dedicated

I might have already posted this but I’m on the Cardinals under 76.5 RSW (-109) at Westgate

Orioles pitching is the big question this season…

They lose Byrnes but they are getting back their lockdown closer Bautista, who was absolutely lights out in 2022 & 2023 before missing all of 2024.

Murphy’s Best

EOG Dedicated

Starting pitching I should have said.

This team is so one player reliant. Did they dodge a bullet? Maybe, but a bad forearm bruise still isn't good for a hitter.

www.espn.com

www.espn.com

Royals' Witt avoids forearm fracture after HBP

Royals shortstop Bobby Witt Jr. suffered a bruise when he was struck on the left forearm by a 95 mph fastball and left Wednesday's spring training game.

Patrick McIrish

OCCams raZOR

Speaking of Royals, that dude they drafted 6th overall is just crushing! Knocking the cover off the ball.

Yeah he's a Gator but I really believe he's the real deal.

He will have a quick trip through the minors.

Yeah he's a Gator but I really believe he's the real deal.

He will have a quick trip through the minors.

kane

EOG master

He's also another one on the Red Sox band wagon -115 to make the playoffsIn case you missed it this morning, Krackman is heavy on Twins to miss playoffs -125.

kane

EOG master

Despite where he went to school, there's a lot to like about the kid. He's been impressive this Spring, more than likely he'll start the season in the minors, but I expect at some point he'll get called up, I just made a ROY future on him +5000, if by some chance he makes the team to start the season, those odds won't be there. He plays first base and right now he's blocked by Pasquantino, but if he mashes in the minors, they'll find a spot for him, he could DH or play him in the outfield, it isn't often I root for a Gator, but it's easy to see the potential he hasSpeaking of Royals, that dude they drafted 6th overall is just crushing! Knocking the cover off the ball.

Yeah he's a Gator but I really believe he's the real deal.

He will have a quick trip through the minors.

kane

EOG master

I made a pizza bet on Sasaki CY +7500. I haven't seen him live, just highlights, but I can see why there's so much hype, he's got filthy stuff, I wasn't planning on betting him, but at those odds, with a pitcher as nasty as he is, on a team that's as good as the Dodgers will be be, I couldn't pass it up

pro analyser

EOG Dedicated

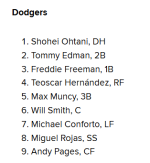

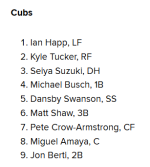

not the lineups.

dodgers are tough...the cubs gave up 8 walks

not the lineups.

dodgers are tough...the cubs gave up 8 walks

Yep. Freeman was out. MLB career high in walks for Imanaga.

Marlins Under 63.5

Is Matt Mervis really the clean up hitter for the Marlins?

kane

EOG master

Not sure where he's batting in the lineup, but he's expected to split time at first with Jonah Bride. The other day I saw the Marlins projected lineup and rotation, all I can say is this year's Marlins might be last year's White Sox, bad doesn't begin to describe this roster, and at some point, probably sooner than later Sandy gets movedIs Matt Mervis really the clean up hitter for the Marlins?

Not sure where he's batting in the lineup, but he's expected to split time at first with Jonah Bride. The other day I saw the Marlins projected lineup and rotation, all I can say is this year's Marlins might be last year's White Sox, bad doesn't begin to describe this roster, and at some point, probably sooner than later Sandy gets moved

A good prop might be who will lose the most games? White Sox, Marlins and Rockies. I know the RSW totals say the White Sox, but I don't believe that's a lock.

kane

EOG master

Marlins projected SL

SS Xavier Edwards

3B Connor Norby

RF Griffin Conine

DH Jonah Bride

1B Matt Mervis

2B Otto Lopez

LF Kyle Stowers

C Nick Fortes

CF Derek Hill

Rotation

Sandy Alcantara

Max Meyer

Cal Quantrill

Connor Gillispie

Valente Bellozo

Closer

Calvin Faucher

Quite possibly the worst lineup and rotation in MLB

SS Xavier Edwards

3B Connor Norby

RF Griffin Conine

DH Jonah Bride

1B Matt Mervis

2B Otto Lopez

LF Kyle Stowers

C Nick Fortes

CF Derek Hill

Rotation

Sandy Alcantara

Max Meyer

Cal Quantrill

Connor Gillispie

Valente Bellozo

Closer

Calvin Faucher

Quite possibly the worst lineup and rotation in MLB

FairWarning

Bells Beer Connoisseur

Dark horse - Angels.A good prop might be who will lose the most games? White Sox, Marlins and Rockies. I know the RSW totals say the White Sox, but I don't believe that's a lock.

probably play the White Sox under 52.5. They have no talent at all.

kane

EOG master

No killer team? I don't know Topper, the Braves and Phillies look pretty good to me, and if the Mets pitching holds up, they're dangerous as wellyes IMO the marlins will be bad but the rest of the division is very good but no killer team. The rockies could be worse than miami

No killer team? I don't know Topper, the Braves and Phillies look pretty good to me, and if the Mets pitching holds up, they're dangerous as well

IMO they are a step below the dodgers...IMO the dodgers are the only killer team in MLB

don't get me wrong the phillies and braves are very good

FairWarning

Bells Beer Connoisseur

Still, how many wins will they get vs Atl, NY, and Philly - 15 total?IMO they are a step below the dodgers...IMO the dodgers are the only killer team in MLB

don't get me wrong the phillies and braves are very good

I don't know how many times the Marlins will be favored this year, some of the games that Sandy pitches maybe, but that's it

i just think they have an easier time than colorado

i just think they have an easier time than colorado

But Colorado always has a home field/park advantage. All Denver teams do. The Marlins have no home field advantage.

kane

EOG master

Exactly. For as bad as the Rockies are, playing half their games at Coors is an equalizer, they should win enough 8-7 games to keep them above the Marlins, I would be surprised if the marlins aren't the worst team in the NL and possible MLBBut Colorado always has a home field/park advantage. All Denver teams do. The Marlins have no home field advantage.

mr merlin

EOG Master

I'd say 2Is there a prop on how many teams lose 100 or more? I would say 3.

But Colorado always has a home field/park advantage. All Denver teams do. The Marlins have no home field advantage.

yes very true, but i was looking at the competition of each

Stu Sternberg, owner of the Tampa Bay Rays, has backed out of a deal to build a new stadium in St. Petersburg, Florida, with $600 million in taxpayer funding, infuriating local officials. The decision has raised the possibility of the franchise being sold and relocating to another city, with other cities in Florida and elsewhere expressing interest in hosting the team. The Rays are currently without a permanent home, set to play the 2025 season at the Yankees' spring training facility, and their future in St. Petersburg is uncertain.

Stu Sternberg and St. Petersburg, Florida, were meant to have a deal.

The former financier and owner of the Tampa Bay Rays (not based in Tampa) would get $600 million of taxpayer money to help keep the Major League Baseball team in the city of St. Petersburg. Pitches to relocate to Tampa and Montreal were thwarted and months of negotiation led to the approval of a controversial debt sale.

The result should have been a $6.5 billion development in a historically Black neighborhood in the Gulf Coast city, with a new stadium, shops and apartments. But then, Sternberg bailed, infuriating local officials who are now refusing to deal with him — raising the specter of the franchise being sold and relocating to another city.

“The deal they are walking away from cannot be recreated,” said St. Petersburg Mayor Ken Welch. He said Sternberg called to inform him of the decision the same day the Rays posted a statement on X saying they would not go ahead with its new ballpark, referencing the impact from hurricanes that hit the state last fall.

The conversation was short and included no explanation for the reversal, Welch said.

A spokesperson for the team declined to comment on behalf of the Rays and Sternberg.

“I don’t know why they chose to pull out after years of negotiations,” said Welch. “It doesn’t make sense to me on several fronts.”

The decision underscores the fraught dynamics at play when cities negotiate with professional sports franchises. Local governments are often cautious about allocating too much to a team, given other spending needs and taxpayer appetite for funding such enterprises. Meanwhile, teams can threaten to relocate to other cities that are prepared to invest and provide taxpayer-funded subsidies.

Sternberg — a former partner at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. — has been exploring a new stadium for almost 20 years. Tropicana Field, known locally as the Trop, opened in 1990 and has been the home of the Rays since the team’s inaugural season eight years later. It’s dingy and outdated, and before Hurricane Milton blew a hole in the ceiling in October, it was the only active MLB ballpark with a non-retractable roof.

While his name is at the center of this deal, Sternberg’s presence has been scant. Local officials said that they had only encountered him briefly, and that he mostly deployed Rays’ co-presidents Brian Auld and Matthew Silverman to liaise with the community. Silverman is a former Goldman colleague and helped Sternberg orchestrate his purchase of the franchise.

Since the team’s reversal, MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred has been doing damage control, assuring several local officials the organization is committed to staying in Florida. And his proposal to expand the league is contingent on the Rays securing a new ballpark. Both Nashville and Salt Lake City have groups lobbying for a team.

Other cities in Florida haven’t wasted time, hinting they would be open to conversations. An Orlando group led by former Cincinnati Reds shortstop Barry Larkin said they have identified an anchor investor to support their expansion bid just days after Sternberg’s retreat. And Tampa Mayor Jane Castor said they’re open to restarting negotiations with the Rays.

“There’s a reasonable likelihood that the team will move out of St. Pete, but one of the problems is that you have to find another city that has the demographic and economic clout that greater Tampa Bay has,” said Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College.

Possible Sale

Constructing a ballpark in the Tampa area comes with a built-in set of challenges, namely strong storms that threaten the infrastructure. The team suggested last year’s hurricanes raised construction costs for the new stadium by as much as $300 million.

The experience identified the lack of climate-fortified infrastructure, said Welch. “We’ve got other priorities than a professional sports team.”

As the debate over the future of the Rays continues to unfold, the prospect of relocating the team, or selling it, grows more tangible.

Mayor Welch said he was recently approached by ownership groups contemplating bids for the franchise. Without the team tied to the deal, a new owner would be able to build outside of St. Petersburg, in a larger Florida city or out of the state entirely.

The team is currently valued at $1.25 billion, according to Forbes, a far cry from the $200 million Sternberg bought the team for in 2004.

Under his ownership and a Wall Street-like approach to management, the Rays have been one of the more successful franchises in baseball. They’ve boasted a winning record in 12 of their last 17 seasons and won the American League East in 2008, 2010, 2020 and 2021.

Despite the team’s success, the Rays averaged a mere 16,515 fans a game in 2024. That’s the third-worst attendance in the league, better than only the Miami Marlins and Oakland Athletics. And the last time the Rays competed in the playoffs in 2023, their Wild Card Series opener drew roughly 20,000 fans, the lowest for a postseason game since the 1919 World Series, excluding those played during the coronavirus pandemic.

Between the botched deal and the hurricane-damaged stadium in St. Petersburg, the Rays are somewhat homeless for the foreseeable future. They’re set to play the 2025 season at the Yankees’ spring training facility, which holds about a quarter of the fans compared to the Trop.

As the owner of the stadium, St. Petersburg is footing the bill to repair the roof at Tropicana Field. Welch said they aim to reopen the stadium for the 2026 season, but noted they aren’t required to do so.

The former financier and owner of the Tampa Bay Rays (not based in Tampa) would get $600 million of taxpayer money to help keep the Major League Baseball team in the city of St. Petersburg. Pitches to relocate to Tampa and Montreal were thwarted and months of negotiation led to the approval of a controversial debt sale.

The result should have been a $6.5 billion development in a historically Black neighborhood in the Gulf Coast city, with a new stadium, shops and apartments. But then, Sternberg bailed, infuriating local officials who are now refusing to deal with him — raising the specter of the franchise being sold and relocating to another city.

“The deal they are walking away from cannot be recreated,” said St. Petersburg Mayor Ken Welch. He said Sternberg called to inform him of the decision the same day the Rays posted a statement on X saying they would not go ahead with its new ballpark, referencing the impact from hurricanes that hit the state last fall.

The conversation was short and included no explanation for the reversal, Welch said.

A spokesperson for the team declined to comment on behalf of the Rays and Sternberg.

“I don’t know why they chose to pull out after years of negotiations,” said Welch. “It doesn’t make sense to me on several fronts.”

The decision underscores the fraught dynamics at play when cities negotiate with professional sports franchises. Local governments are often cautious about allocating too much to a team, given other spending needs and taxpayer appetite for funding such enterprises. Meanwhile, teams can threaten to relocate to other cities that are prepared to invest and provide taxpayer-funded subsidies.

Sternberg — a former partner at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. — has been exploring a new stadium for almost 20 years. Tropicana Field, known locally as the Trop, opened in 1990 and has been the home of the Rays since the team’s inaugural season eight years later. It’s dingy and outdated, and before Hurricane Milton blew a hole in the ceiling in October, it was the only active MLB ballpark with a non-retractable roof.

While his name is at the center of this deal, Sternberg’s presence has been scant. Local officials said that they had only encountered him briefly, and that he mostly deployed Rays’ co-presidents Brian Auld and Matthew Silverman to liaise with the community. Silverman is a former Goldman colleague and helped Sternberg orchestrate his purchase of the franchise.

Since the team’s reversal, MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred has been doing damage control, assuring several local officials the organization is committed to staying in Florida. And his proposal to expand the league is contingent on the Rays securing a new ballpark. Both Nashville and Salt Lake City have groups lobbying for a team.

Other cities in Florida haven’t wasted time, hinting they would be open to conversations. An Orlando group led by former Cincinnati Reds shortstop Barry Larkin said they have identified an anchor investor to support their expansion bid just days after Sternberg’s retreat. And Tampa Mayor Jane Castor said they’re open to restarting negotiations with the Rays.

“There’s a reasonable likelihood that the team will move out of St. Pete, but one of the problems is that you have to find another city that has the demographic and economic clout that greater Tampa Bay has,” said Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College.

Possible Sale

Constructing a ballpark in the Tampa area comes with a built-in set of challenges, namely strong storms that threaten the infrastructure. The team suggested last year’s hurricanes raised construction costs for the new stadium by as much as $300 million.

The experience identified the lack of climate-fortified infrastructure, said Welch. “We’ve got other priorities than a professional sports team.”

As the debate over the future of the Rays continues to unfold, the prospect of relocating the team, or selling it, grows more tangible.

Mayor Welch said he was recently approached by ownership groups contemplating bids for the franchise. Without the team tied to the deal, a new owner would be able to build outside of St. Petersburg, in a larger Florida city or out of the state entirely.

The team is currently valued at $1.25 billion, according to Forbes, a far cry from the $200 million Sternberg bought the team for in 2004.

Under his ownership and a Wall Street-like approach to management, the Rays have been one of the more successful franchises in baseball. They’ve boasted a winning record in 12 of their last 17 seasons and won the American League East in 2008, 2010, 2020 and 2021.

Despite the team’s success, the Rays averaged a mere 16,515 fans a game in 2024. That’s the third-worst attendance in the league, better than only the Miami Marlins and Oakland Athletics. And the last time the Rays competed in the playoffs in 2023, their Wild Card Series opener drew roughly 20,000 fans, the lowest for a postseason game since the 1919 World Series, excluding those played during the coronavirus pandemic.

Between the botched deal and the hurricane-damaged stadium in St. Petersburg, the Rays are somewhat homeless for the foreseeable future. They’re set to play the 2025 season at the Yankees’ spring training facility, which holds about a quarter of the fans compared to the Trop.

As the owner of the stadium, St. Petersburg is footing the bill to repair the roof at Tropicana Field. Welch said they aim to reopen the stadium for the 2026 season, but noted they aren’t required to do so.